Make What’s Safe Legal and What’s Legal Safe

We all grow up learning the road rules: look before you cross, give way to the right, don’t drive too fast. They’re framed as lessons in safety but in truth, most of them aren’t really about keeping us safe at all.

The Real Purpose of Road Rules

Road rules exist to enable fast travel. Inside a shopping mall, there are no lanes, no signals, no rules. Children running around a playground don’t give way to the right; they negotiate space through micro movements, instinct, and eye contact. But once speed and heavy machinery (read kinetic energy) enter the picture, we need a system of rules to keep the chaos manageable. Road rules were invented not to keep pedestrians alive, but to allow cars to go fast.

But cars are big, heavy, and capable of immense harm. Having them roam around the city without due regulation is a terrible idea. The rules we have in place are clearly effective at reducing harm to people on our streets and roads. However, it is madness to apply the same rules to people riding bicycles.

When the Law Gets It Wrong

Bicycles aren’t small cars. They’re not fast pedestrians either. They exist in a space of their own, somewhere between the two. Yet most of our cities treat them as if they belong squarely on the side of the motorist. Even cities that tout themselves to be “bike-friendly” remain, at heart, car-centric. Footpaths are for walking; roads are for cars and, by legal extension, bicycles. The bike lane is treated as a “special vehicle lane” rather than a human space, and the person pedalling through it is considered a more vulnerable driver (and thus should wear a helmet).

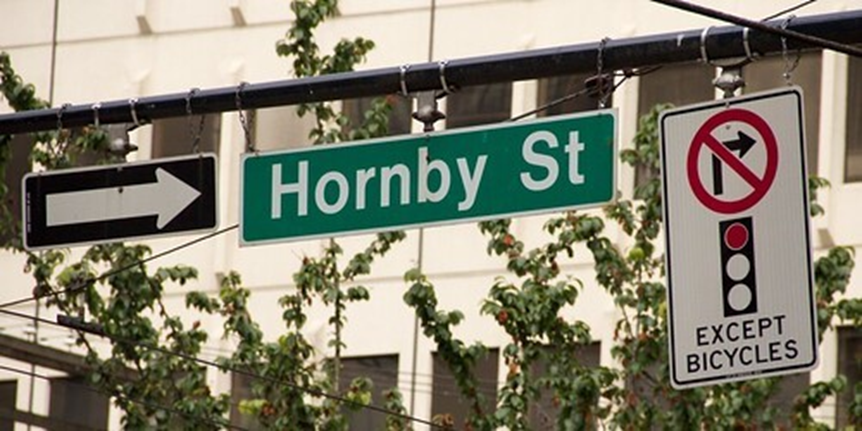

This system creates dangerous situations. Cyclists are bound by laws written for a completely different kind of vehicle. Laws that can make the safe thing illegal and the legal thing unsafe. Breaking those rules can invite fines or accusations of being a “scofflaw cyclist.” But obeying them can mean putting yourself in harm’s way.

A Daily Dilemma

Anyone who cycles in Auckland knows this dilemma well. At almost every intersection, I face a choice: follow the rules, or take the safe route. It is often far safer to move when the pedestrian light turns green rather than waiting for the car light to turn green, to use a quiet footpath instead of a hostile road, or to turn left on a red light rather than risk conflict with a motor vehicle. These decisions aren’t acts of rebellion; they’re sensible acts of self-preservation.

Rethinking the System

The problem isn’t the cyclist, it’s the system. Our cities are built on a bi-modal model that recognises only two kinds of movement: walking and driving. But if we want cycling to be truly safe and accessible, we need to move towards a tri-modal system. A system that acknowledges cyclists as a distinct class of road user with their own needs, risks, behaviours, and rules.

That doesn’t mean allowing scofflaw cyclists to do whatever they please. It means introducing evidence-based regulation that prioritises minimising risk to others and to society as a whole. Pedestrians and cyclists can safely negotiate shared space through human interaction; cars, with their weight and speed, pose the real hazard. By making safe behaviour legal, we allow cyclists to think for themselves and keep themselves safe.

Making Safety the Standard

In a city where cycling infrastructure is inconsistent, incomplete, or simply unsafe, expecting cyclists to adhere strictly to car rules is unrealistic, unfair, and dangerous. Instead, the law should adapt to reality: make what’s safe legal. What follows is a system that starts by designing for the safe behavior cyclists exhibit, allowing us to create what’s legally safe.

At Mobycon, we help cities around the world create designs that prioritize human safety and truly embrace cyclists’ needs. If you’re ready to evolve your city’s infrastructure to support safer behavior and cycling happiness, reach out to us to learn about our customized Masterclasses, Study Tours, and consulting services.