Cycling / Diversity / Mobility

Why Diversity is Important in the Cycling Industry

Strategic Advisor Angela van der Kloof recently participated in the International Cargo Bike Festival (ICBF). She spoke on a panel about diversity in the cycling sector, and in this blog she reflects on her key takeaways from the event about the importance of diversity.

Recently, I participated in the International Cargo Bike Festival (ICBF), a vibrant yearly event organized by the ever-enthusiastic and knowledgeable Jos Sluijsmans and Tom Parr. The event was a great combination of a program filled with interesting speakers and topics, a fair with various models for (primarily electric) cargo cycles, a test track, and opportunities to set up meetings. At the festival, I participated in the panel discussion ‘Diversity in the cargo bike industry and cycle logistics’ with the Founder of Nüwiel Natalia Tomiyama, and Eileen Niehaus, manager at cargobike.jetzt. The panel was led by Margot Daris from the Dutch Cycling Embassy.

In the panel, we shared what diversity means to us and why it’s an important topic at ICBF. Diversity comes down to the question of who is represented. Who is represented in the workforce, in the images used in brochures, and in the types of products offered? This matters since it affects how people view themselves and whether their needs are considered. Little to no representation can make potential workers, collaborators, and clients wonder whether the job offer, product, or system is set up for people like them.

Diversity is not just about having a balanced gender representation. It is also about age diversity, ethnic diversity, diversity in physical ability, and neurodiversity. Research shows that a diverse workforce creates a better chance to have a mix of experiences, knowledge, and ways of thinking, which corresponds with performance. Gender and ethnically-diverse companies perform better financially because when the representation of gender diversity is better, the likelihood of outperformance is higher.

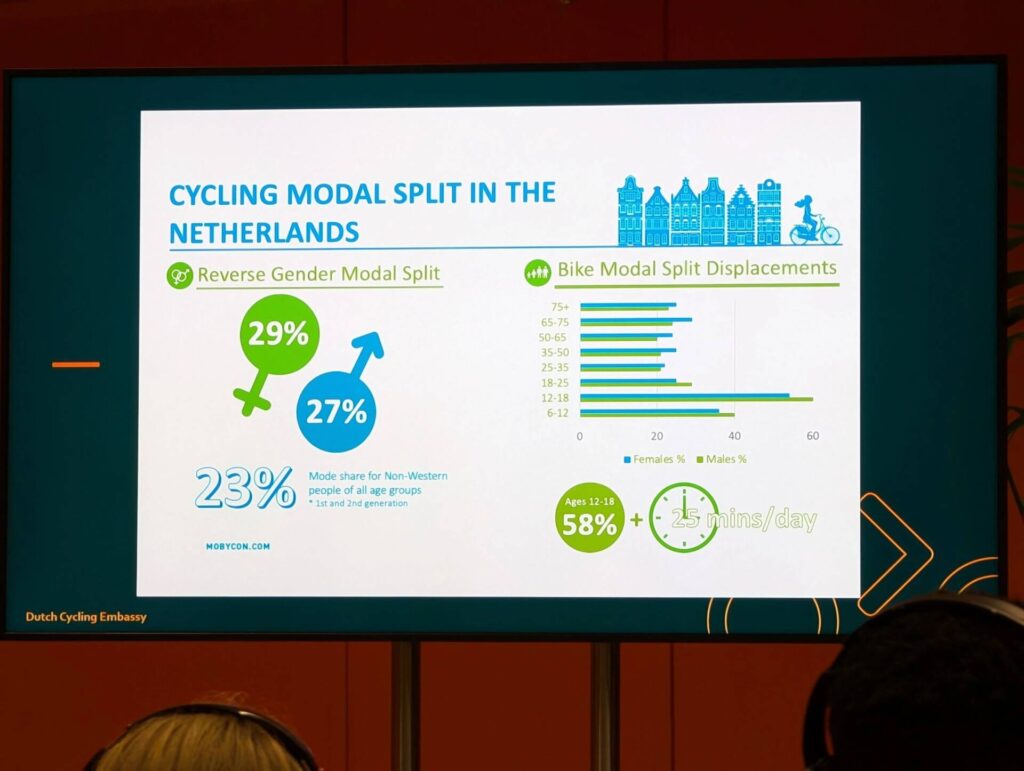

Until now, there has been no research on diversity in the cargo bike industry and cycle logistics. We need to find out the percentage of women who work in the sector, let alone from other facets of diversity. We also do not have other gender-disaggregated data on cargo bike usage and sales. If we look at the cycling sector as a whole, we know a bit more. For example, we know about the percentage of trips made by cycle by gender and age in the Netherlands. For the topic of diversity, it is interesting to note that we have a reverse gender and age gap in the modal split in the Netherlands, compared to other countries.

As of 2023, the percentage of trips by bicycle in the modal split for women in the Netherlands is higher (29%) compared to men (27%). This number is particularly fascinating when comparing the ages of women aged 25-75+, where the percentages of trips by female cyclists outnumber the percentages of trips by male cyclists in this age range. The age group who cycles the most are children aged 12-18, where 58% of children in this age group cycle for up to 25 minutes per day (source: https://www.cbs.nl/).

When it comes to diversity in the workforce, the only relevant figures that I know of, are that women make up >50% of the EU population, while less than 20% of workers in the transport field are women (source, see page 42).

This picture is confirmed by ‘The Diversity Perception Survey‘ commissioned by The Bicycle Association in the UK. It showed that the overrepresented majority of workers in the cycling industry are white, heterosexual males. The survey also found that minority groups feel marginalized. They found a worrying number of reports of unfair treatment (incl. bullying and harassment). Eight in ten women face barriers to progressing their careers in the cycling industry, and only half believe they are paid the same as men for the same role. Another finding was that just half of ethnic minority respondents felt free to be themselves at work, versus 84% of white respondents. The report suggests that there is an underlying culture in the industry that is indifferent to discrimination, exclusion, and intolerance. This means that a lot of work needs to be done if we want the sector to be diverse and inclusive.

Another interesting angle to look at diversity in the field of cargo bikes and cycle logistics was sparked by the question how cycling has changed since the 1990s (when I started to work in cycling projects). Back then, people who worked on promoting cycling were seen as alternative hippies who wore goats’ woolen socks. If I talked with people about the activities I was setting up in a cycling school for (migrant and refugee) women in my city in the Netherlands, I was often laughed at, and people were puzzled how I could choose this path while I had a teaching degree and a Masters degree.

In the last ten years, working in the cycling sector in the Netherlands has a much more fashionable and fresh image. This is linked with two directions I have seen emerge in the cycling sector. First, there is the direction of fast cycling. This is about efficiency, cycling as a competitive mode for driving, cycling highways, and more complicated technology. It centers around technical innovation, speed, and no hurdles. It doesn’t challenge power relations in our society. The second direction is slow cycling. This narrative is about connecting with other humans and the environment, where cycling is for everyone. This direction centers around social innovation and social change. It is about the work that needs to be done to shift away from serving only the groups that already have multiple mobility options to those with less access to resources and mobility options.

Interestingly enough, both directions, the fast efficient one and the slow social one were represented at the exhibition. There were cargo bikes for families, other social bikes suited for multiple people, and fast personal and delivery cargo bikes. It is important to acknowledge this dichotomy in the cycling field and understand that there is a risk that fast cycling will dominate slow cycling at some point. This risk is real since fast cycling aligns well with the values that underly car-centric development and moto-normative assumptions. The quicker and more efficient (cargo bike) cycling gets, the more there is a risk of moving away from the social benefits of cycling.

Ultimately, the strength of cycling lies in its ability to connect humans with each other and their environment while they’re on the move. We’ll have to find a way to embrace fast cycling. This helps us move away from car dependence while at the same time taming it in the places where slow cycling can flourish in conjunction with walking and good quality public space.