Accessibility / Walking

Partaking in the ultimate pedestrian experience: El Camino de Santiago

This year I’ve checked one more thing off the archetypical millennial bucket-list: El Camino de Santiago. No, I didn’t quit my job and take off to “find myself” by wandering the well-trodden paths of many pilgrims before me with The Alchemist in hand. I quite simply wanted to do something active and social during a two-week holiday to clear the head, while also soaking up some vitamin-D before winter drains it out of me.

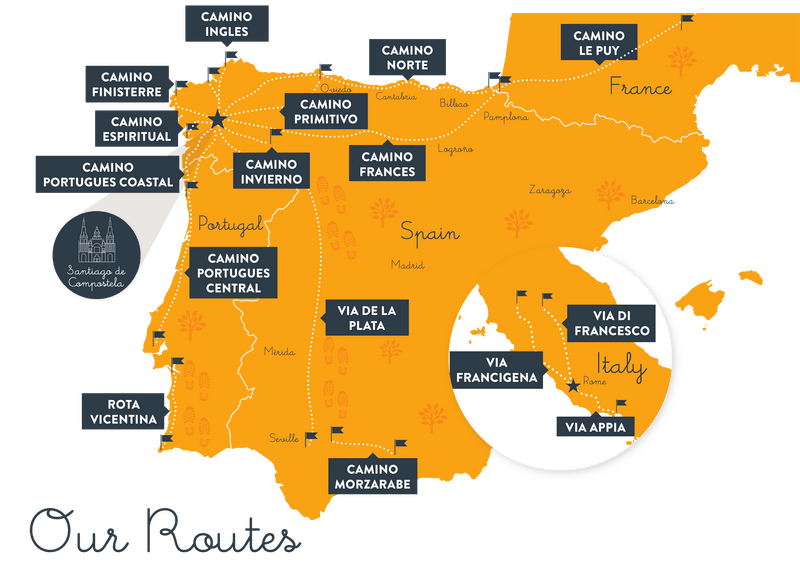

El Camino de Santiago Route Maps (Source: caminoways.com/camino-de-santiago)

The most common route is called the “French Way” (el Camino Francés), crossing through Northern Spain from France, however I opted for the “Portuguese Way” (el Camino Portugués) as I had never been to Portugal. Seeking hills and forest, I opted for the central route, heading directly north, passing through the occasional village and stopping in modest inns (albergues) for sleep and a warm shower (if you’re lucky). In other words, I wanted something ‘off the beaten path’.

While walking the two hundred or so kilometres from Porto to Santiago de Compostela, I realized that I was, in fact, partaking in the ultimate pedestrian experience. That is, my only mode of transport from place to place was my own two feet, be that on asphalt, dirt paths, or the ancient roman cobblestone roads much of the route followed. During that time, I was constantly reminded of the importance of high-quality pedestrian infrastructure.

Photo credit: Isabel Macedo

Wayfinding matters*

Not once, during the entire journey, did I take a wrong turn. The wayfinding system of the Camino is quite rudimentary, but its visual and geographic consistency makes it effective. At its most basic, yellow arrows are painted on walls, rocks and fences indicating the route. These share the colour of the ubiquitous traditional yellow scallop shell symbol of the Camino, which can be found on many St. Jacob trails throughout Europe (including the Netherlands). These visual elements, both colours and symbols, return again and again throughout the route, reminding pilgrims that they’re on the right track.

In addition to the yellow arrows, stone pillars marked with the same symbol also indicate the remaining distance to Santiago de Compostela. This ‘distance to’ aspect of wayfinding should not be overlooked, giving the user an idea of how far (and how much time) is remaining in their journey. Normally, an estimated time to your destination is quite helpful, however, at longer distances, travel time can differ significantly per person – depending on how many blisters you have!

The Importance of Rest

At such long distances, rest is important. Not just a good night’s sleep, but stopping every few hours to eat and drink, take the pressure of your legs, and tend to your battered feet. If you time your breaks right, a small rural café will have chairs, tables, carbs, and the caffeinated beverage of your choice. Yet, there are still areas where you might walk five or six kilometres with no café in sight. In this case, the bare earth or a conveniently shaped rock will do, but a well-placed park bench or picnic table is welcome gift from the Camino gods.

Of course, this also applies to shorter recreational routes, though is often overlooked for more utilitarian walking purposes. This is to say, rest points are important especially (but not only) for recreational routes. While my relatively young and non-disabled self might not need to stop and rest during the ten-minute walk to the supermarket, others might, and a well-placed bench or seat might make the difference between walking to the shop versus going by car or public transport.

Sidewalk Slalom

Urban environments tend to contain higher densities of destinations. That is after all, part of the reason cities are, well, cities. All these destinations need to be accessed by users, however, “access” all too often first assumes car access, resulting in entrances and exits designed with smooth ramps guiding vehicle traffic straight up to the destination – usually a *parking lot. In these instances, the sidewalk is raised slightly above the roadway, making crossing these access points a series of peaks and valleys that make for not only for uncomfortable stroll, but also limit access for more vulnerable pedestrians such as the those in wheelchairs or those less stable on their feet.

The journey has value in itself

These elements also say something about the quality of a route. Mobility – particularly active modes such as walking and cycling – is not just about getting from A to B as efficiently as possible. In fact, it has been found that cyclists will often choose a route that is not necessarily the most direct to their destination but instead one that is most pleasant. In other words, our mobility activity has value in and of itself. Unfortunately, this value is scarcely exploited, as most of the world’s existing transport networks are not designed for a high-quality journey, but instead for moving people as fast as possible from A to B.

Urban planning lessons aside, walking for two weeks was a surprisingly rejuvenating way to spend my holidays. The Portuguese and Spanish sun was a welcome treat, and I most definitely learned to appreciate the satisfying simplicity of a walk, whether at twenty kilometres or a lunchtime stroll.

Photo credit: Isabel Macedo

Picturesque. It could be a postcard. What it doesn’t show are the repetitive swooshes of cars passing on a highway nearby, along with the occasional honk of a lorry. But I wouldn’t exchange the experience for anything!

*Learn more about wayfinding in this Mobycon Academy webinar with Stephen Kurz and Mary Elbech

">

">Stephen Kurz

‘Though we are strongly influenced by our environment, effective urban design can help us make sustainable, healthy, and safe choices. Not because we’re more aware of our choices, but because we’re not. Good urban design makes the ‘right’ choice easy. To achieve this, I value non-traditional approaches to exploring and developing solutions to urban issues.’