Conference / Cycling

"The cycle path is not a long, quiet river": 5 misconceptions about cycling urbanism

In French, to compare something to a long, quiet river means that it’s going according to plan, with no surprises or jolts. Living in the Netherlands, every day I experience what this phrase means when applied to cycling. In many other countries, on the other hand, we cannot yet use it. However, we should not assume that this has always been the case in the Netherlands…

The cycle path has not always been a “long quiet river” in the Netherlands. This image shows a demonstration in Amsterdam in the early 1980s, attended by over 15,000 people protesting against the “autoterror” (Source: National Archief).

At the 25th anniversary of my university curriculum (“Urban Engineering” at the Compiègne University of Technology), I presented to an audience of former and future engineering graduates, sharing a few keys to understanding the Dutch cycling model. In this article, I will present five preconceived ideas (and there are many more!) about cycling mobility, to be invalidated or nuanced, to make our cycling journeys ever more comparable to a long, tranquil river.

Presenting at the 25th anniversary of UTC’s Urban Engineering program. (Source: Author)

1. “In the Netherlands, they have been cycling forever”

The (re)emergence of cycling in the post-war Netherlands did not happen overnight, but rather can be explained by the implementation of a nationally-coordinated structural policy and substantial investment. This pro-bicycle policy took root at the turn of the 1970s, at a time when the number of road deaths caused by cars and the price of oil were both hitting record highs. Under pressure from civil movements and a strained energy supply, the bicycle emerged as the obvious, low-cost, and familiar solution on which the Dutch government would build its current worldwide reputation.

2. “In France (or anywhere else), there is not enough room to build bike paths”

The root of the problem lies not in a lack of space, but in our approach to making choices and defining network priorities. Cycle paths are often considered to be the key feature of a cycle-friendly city. Ideally, however, they should represent only 20% of an urban network, with the remaining 80% allowing for a mix of modes. The real challenge, then, is to determine what we want to do with our public spaces, and to get the rolling metal boxes that we call cars out of the places where we want to see vegetation, social interaction, and ground-floor activities flourish.

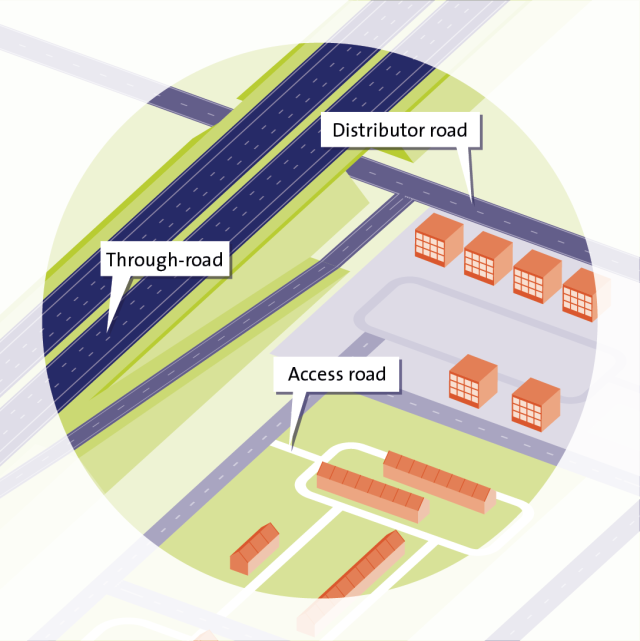

In the Netherlands, according to the principle of hierarchy (derived from the Sustainable Safety paradigm), the choices made at the network level are made explicit through road design. For each of the three designated categories of road (through, distributor, or access), there are specific design elements (harmonized nationwide) that help to ensure users respect the behaviour expected of them.

The categorization of roads in the Netherlands makes public space easier to understand and share. (Source: SWOV)

3. “Bicycle facilities are calibrated to the average user”

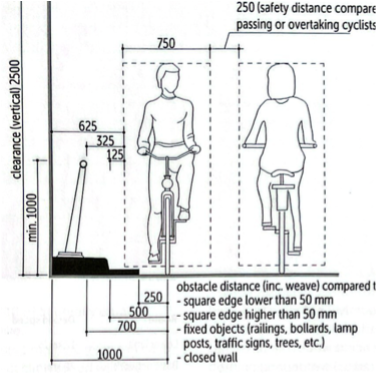

In the Dutch Bicycle Traffic Design Manual published by the CROW, the necessary clearance for a moving cyclist is around 75 cm. When setting standards, it is necessary to establish average dimensions that will suit most users. However, the benefit of the Dutch cycling model is that it favours not just one type of user, but all users (see picture below)! Bicycle facilities are then designed to accommodate those who need it most – such as those who are new to cycling or may be less confident in their abilities (children, women, elderly) – requiring the development of high standards and a resilient cycling network. Accordingly, lanes are often designed wide enough to allow two cyclists to ride side-by-side, reinforcing cycling as a social practice.

Standard safety dimensions for bicycle traffic. (Source: CROW)

The average cyclist does not exist! (Source: DCE)

4. “Cycling urbanism is a revolution in public space”

You have probably already seen images of the Hovenring (a suspended cycling traffic circle) or the Daphne Shippersbrug (a cycling bridge integrated into a school); two iconic cycling infrastructures located in Eindhoven and Utrecht, with the latter city also having the world’s largest bicycle parking garage and being the showcase city for Dutch-style cycle planning. Although these images leave their mark on the mind and contribute to the transformation of one’s imagination, urban cycling does not generally require enormous resources. The COVID crisis, for example, illustrated just how quickly and inexpensively it was possible to make changes to our public spaces, notably through tactical/temporary infrastructure (as was the case for rue de Rivoli in Paris).

Not only a revolution in public space, cycling urbanism is also a revolution in time. It’s about valuing cyclists’ time as much, if not more, than motorists’ (thanks to dynamic display information panels in parking lots or before ferry boarding, for example). It also means taking into account the physical constraints associated with cycling by minimizing gradients, stops, detours, etc.

Dynamic display in stations to quickly find out where to park your bike so you do not miss your train! (Source: DCE)

Example of a FietsDRIP (Dynamic Route Information Panel for cyclists) upstream of the ferry pontoons in Amsterdam (Source: Verkeersnet)

5. “Designing bicycle infrastructure: it is not rocket science!”

If you are adding markings and paint on a road, indeed, designing cycling facilities will not take much effort, nor cost a lot. But the impact on cyclist safety and mode share will be as low as when trying to reduce traffic speed with a single sign.

Designing cycling infrastructure is based on a paradox. Any successful design work should appear simple at first glance. But behind this apparent simplicity lies a long and meticulous upstream design process based on specific know-how that, here at Mobycon, we wish to spread around the world and share with our clients.

To illustrate this, we can consider logo design. You might wonder: “what do the design of a good bicycle facility and a good logo have in common?” They are both intuitive and self-evident, which is a guarantee of their effectiveness. The cycling infrastructure in the Netherlands incorporates many details that make it recognizable at first glance, intuitive to understand, and with a simple, uncluttered form – just like a good logo. It is a perfect blend of ambition and pragmatism, strategy and engineering, creativity and human needs considerations.

To return to our metaphor at the beginning, most bicycle trips in the Netherlands are comparable to a long, quiet river, not least because the designers have sought to make the cyclist’s mental load as light as possible. Since the second half of the 20th century, the logic that has been applied around the world is to continually make driving easier for motorists. In the Netherlands, this logic is applied to cycling by making explicit road user priority, wayfinding, and navigating conflict with other users, and harmonizing these intuitive design guidelines country-wide.

What do a good logo and a good bicycle layout have in common? Their intuitive, efficient design! (Source: Wikipedia; CROW, modified).

In conclusion, it is because of past technical and political choices, notably the development of a car-centric socio-technical system, that developing cycling urbanism (i.e. public spaces that encourage cycling and, by extension, walking) is now a complex act. It is because of this same technical inertia that cycling urbanism now needs to be thought out via academic research and advisory activities for local authorities, tooled (developing a technical vocabulary and new modes of representation), and passed on in articles such as this one so that, in the long term and outside the Netherlands, a culture and new standards for a dedicated spatial planning approach emerge.

">

">