Bike Strategy / Cycling / Public Spaces / Urban Mobility Design

Tirana continues to create a liveable city after our 2016 workshop

Last week The Guardian published the article Build it and they will come’: Tirana’s plan for a ‘kaleidoscope metropolis’, about current urban development in Tirana, the capital of Albania. The vision of a ‘kaleidoscope metropolis’ may sound vague at first, but current mayor, Erion Veliaj, and Joni Baboci, the city’s head of planning and urban development, explain that their vision is to create a mixed-use density area that gives people opportunities to participate in society. Along with conservation of green space, creating attractive open public spaces and encouraging people to travel on bike and foot, referring to the remains of the cycling culture from the communist era. The vision is a response to the unstructured development of Tirana after the fall of the repressive Hoxha government (from the end of WWII to 1990). It is hard to imagine that in 1990 there were only 200 cars in Tirana, a city of about 300,000 inhabitants at the time. Now there are 200,000 cars and over 800,000 inhabitants. That’s more than two times as many inhabitants, and from one car per 1,500 inhabitants to one car per four inhabitants in less than 30 years!

I visited Tirana back in 2016 with my colleague Lennart Nout and some months later Dick van Veen traveled there too. We had been invited to run workshops on urban cycling, and bring Dutch experience and expertise to city staff, advocates and students. We also contributed to the mobility pillar of the General Local Plan Tirana 2030. As part of our visit we had the opportunity to experience the city by bike with a volunteer guide from Ecovolis, the cycling advocacy group in Tirana that runs a workshop and a low-tech bike rental scheme. This was a good opportunity to see the challenges that Tirana faces.

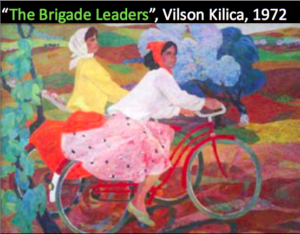

Luckily the visit was also an opportunity to see the remains of the cycling culture from the communist era. Back in 2011, researcher Dorina Pojani presented the paper From Car‐free and Bicycle‐full to Car‐full and Bicycle Free at Velo City in Sevilla, Spain. Pointing out how biking was promoted through communist art and was seen as a sign of emancipation. She noted that the typical bike user in Tirana is male (3 out of 4), a native of Tirana, around 50 years old, with an average income and educational level. Half of men in the city own cars, but thy find bikes more practical for everyday use and 30% commute by bike. During our visit in 2016 we also spotted the typical Tirana bikers, who were riding totally relaxed and comfortable to get groceries or seemed to make other short trips in the neighbourhood.

I hope new generations of people on bicycles in Tirana will be able to fully embrace cycling and also develop a relaxed style of cycling, that fits well with the vision for proximity in the city. I think that it would be worthwhile for us to study how biking was promoted through communist art in Albania and be inspired for the efforts in our own cities.

">

">