Mobility / Mobility management / Public transport / Sustainability / Urban Mobility Design

What could public transport look like after COVID?

The following was originally published on Medium and can be found here: https://blog.bicyclize.com/what-could-public-transport-look-like-after-covid-c92a415702bd

The Dutch bike-transit system should be our guidance to keep public transport not only less loss making, but faster and more attractive by offering higher frequency services with even better coverage. How is that possible?

As we seem to catch the light in the COVID quarantine tunnel many of us question what this might mean to mobility, and particularly to public transport.

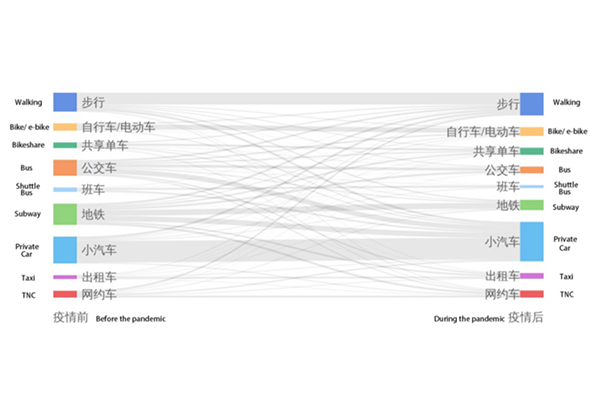

The lock-down in general, had the same impact all around the world: car travel fell 50–80%, public transport plummeted to even more, while cycling and walking had a relative increase.

Asian cities awakening from their winter sleep suggest that the western public will also keep avoiding public transport and instead use a bicycle or walk. What is worrying that car use is also up — understandably, as people try to avoid any contact with anyone — however its impact on air pollution should be a warning to all cities, given that the spread and the fatality rate of COVID has been proven to correlate with air pollution levels.

Let’s draw up in three scenarios where we might be heading to.

1. Carmageddon

Everyone jumps into a car. To ease congestion we build motorways across cities and ban walking and cycling so no pedestrian is killed on the road… well, outside of a car. Issues with this scenario: we have no money either for the in-city motorways, nor to tackle the health issues related to sedentary lifestyle or respiratory disease — like COVID. So hopefully this is a no go zone.

2. Cycle-paradise

We increase the temporary cycling infrastructure network and we turn it into permanent, we create entire networks of car-free zones so that people feel safe to walk and cycle in urban areas. Instead of commissioning bus companies, municipalities contract long-term bike hire companies to rent bikes and e-bikes to the public, like Paris’ Veligo or the Dutch Swapfiets. At €40 or €75 a month it makes an attractive appeal to use an electric bike.

Yes, people with disabilities will have special bikes, elderly ladies will get the fall-proof bikes from Gazelle, and should the weather not be so kind to us as to the Dutch or to the Finnish kids, we shall stay and work from home (or put on a poncho?).

But how likely is it that public transport companies will go down without a political fight, especially when they might be owned by government or the municipality it operates in? What would be the political and social implications of letting these (let’s admit it: unprofitable companies) go?

3. Bike-transit

I do see a third, more rosy scenario for public transport, though: BRT-like operations.

If you are reading this in the developed world and you frequently rode public transport before the lock-down, then you are probably expecting a bus service at your doorstep while waiting no more then 5 minutes. The bus might drop you off at the local transport hub from where you might take the metro to the centre or other parts of town.

With social distancing required in the vehicle and lack of resources to double or triple these services to achieve such low ridership per vehicle we need a novel solution. What we can do however, particularly with buses, is to run them as Bus Rapid Transit buses that take a main corridor only and stop only at few bigger hubs.

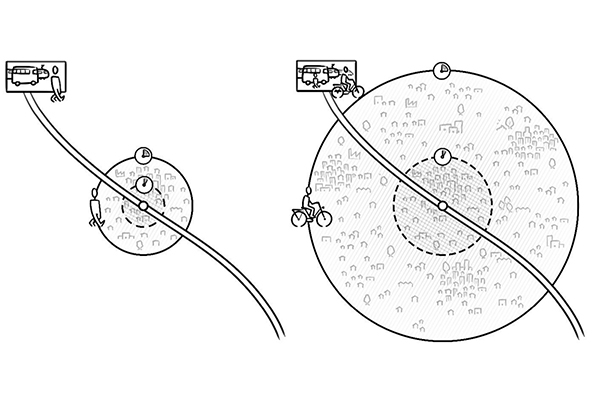

In an extreme case a city could re-allocate all its service to run only BRT’s covering the same area with less routes. Of course this would require passengers to walk 15–20 minutes or, given that cycling is becoming a more accepted mode, they could cycle 5–10 minutes.

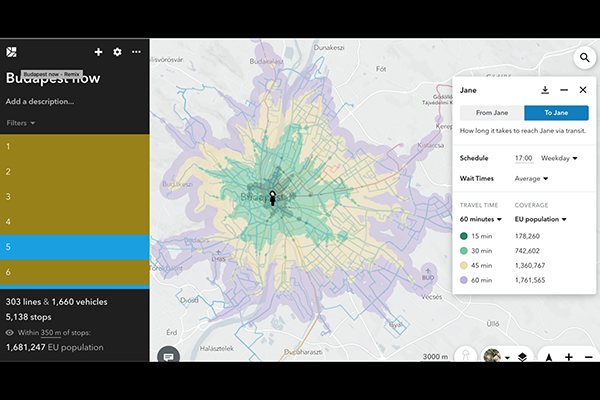

Here is the example of Budapest, a city in Central Eastern Europe with 1.7 million inhabitants within city borders and almost 3 million with agglomeration. Fairly good transit service with extensive bus and tram network, 4 underground lines and 4 suburban rail lines (I will disregard other rail services now). Using Remix’s Transit I made a quick comparison of three scenarios:

Budapest Transit

A. Current conditions

Current accessibility levels, while maintaining 303 lines and 1660 vehicles 1.7 million can reach the city centre (Jane, after Jane Jacobs) within 60 minutes if they reach a stop within 5 minutes — 350 meters.

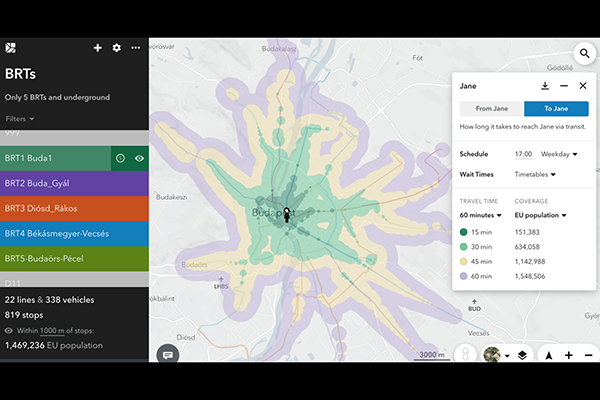

B. BRT lines

Operating only 5 BRTs, keeping underground and suburban railways as is and using only quarter of the vehicles by running every 5 minutes will allow almost the same amount of people (1.5 million) to access the city centre within 60 minutes — provided that they walk 15 minutes to/from the stop.

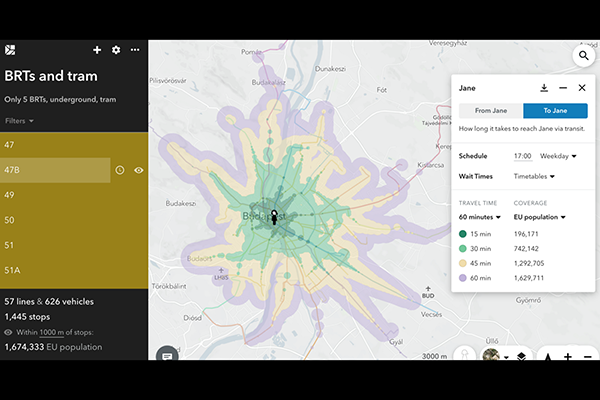

C. BRT + all rail-line services

In this scenario I kept all the 24 tram routes in addition to previous setup, reaching almost as many residents as in current conditions. It’s still not perfect, passengers still need to walk 15 minutes or cycle 5 minutes to reach a stop, but with only a third of the vehicles we could enable almost the same amount of people. Consider that the other 2/3 of the vehicles could provide the social distancing if the 5 minute running frequency would not suffice.

I am not suggesting that you should implement the above as from tomorrow, but I wanted to point out the potential of a public transit system if your passengers do some of the leg-work (sorry, for the pun).

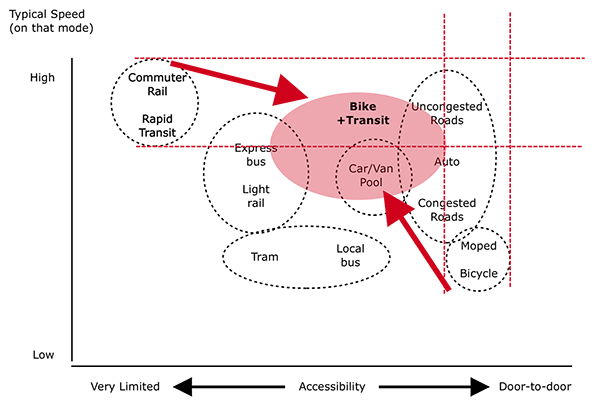

There is ample evidence that bike-transit is a more desired mode than the private motor vehicle. Research from the Netherlands suggests that travellers enjoy the same access and speed levels as a private car, which might explain why half of the rail passengers arrive to the station by bike and quarter leave with a bike. In “peace time” that is.

It is a real transport engineering marvel that has grown its modal share 5% annually in the last 10 years. Much of the credit goes to the OV-fiets, the public transport bike rental scheme, available now at over 300 train stops, allowing passengers to return bicycles to the same station within 24 hours, providing them reliability that they can return the very same way wherever they go.

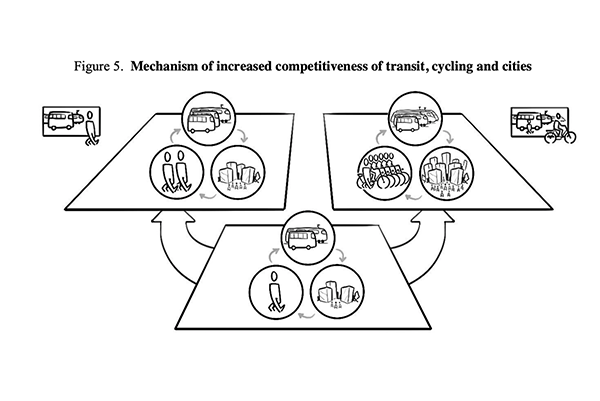

One should notice the Bike-transit scenario overlaps with scenario 2 — Cycling paradise. It’s no wonder, the BRT scenario complements the Cycling paradise scenario, whereas both scenarios mutually exclude the car dependent scenario. Due to the fact that most citizens will cycle 5km’s but not more, they remove the need for local low-level transport (e.g. feeding service) but they reinforce high-level transit systems that depend on the feed. When the public can access (and egress) stations by bike as comfortably as by walking, you multiply catchment areas to those stops.

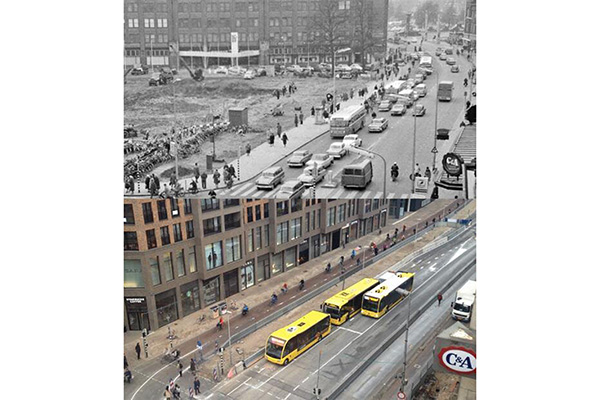

Once the positive reinforcing cycle starts, there is no need for car use in urban areas. Shops turn up at the focal points, eg. around the stations, car-free streets make living conditions pleasant to move to these hubs and the urban sprawl becomes a clustered network of dense villages.

Is it what the 20-minute neighbourhood is all about?