Cycling / Network planning

Traffic Volumes – The Overlooked Factor in Planning a Cycle Network

In planning a safe, comprehensive cycling network, traffic volumes and the way cyclists interact with cars on the road is often overlooked in the North American context. Stephen Kurz argues for applying the Dutch concept of ontvlechten, disentangling and slowing down car traffic to make interactions with cyclists safer.

First the good news: Governments are increasingly recognizing cycling as not just a sport or leisure activity but as a bona fide mode of transportation. It can address many of the contemporary social issues governments face, including infrastructure maintenance costs, accessibility, and health care costs due to lack of physical activity, amongst others. This is great and a step in the right direction.

Now, the not-so-good news: Municipalities who want to improve conditions for cyclists tend to view the cycle network as something that simply needs to be grafted onto their existing transport network. An addition to existing conditions, almost like a cherry on the cake. A street here and there is outfitted with flexpost-protected cycletracks, or parking is removed to make space for permanently protected cycle paths. Emphasis remains on on-street infrastructure measures rather than on structural changes to the network.

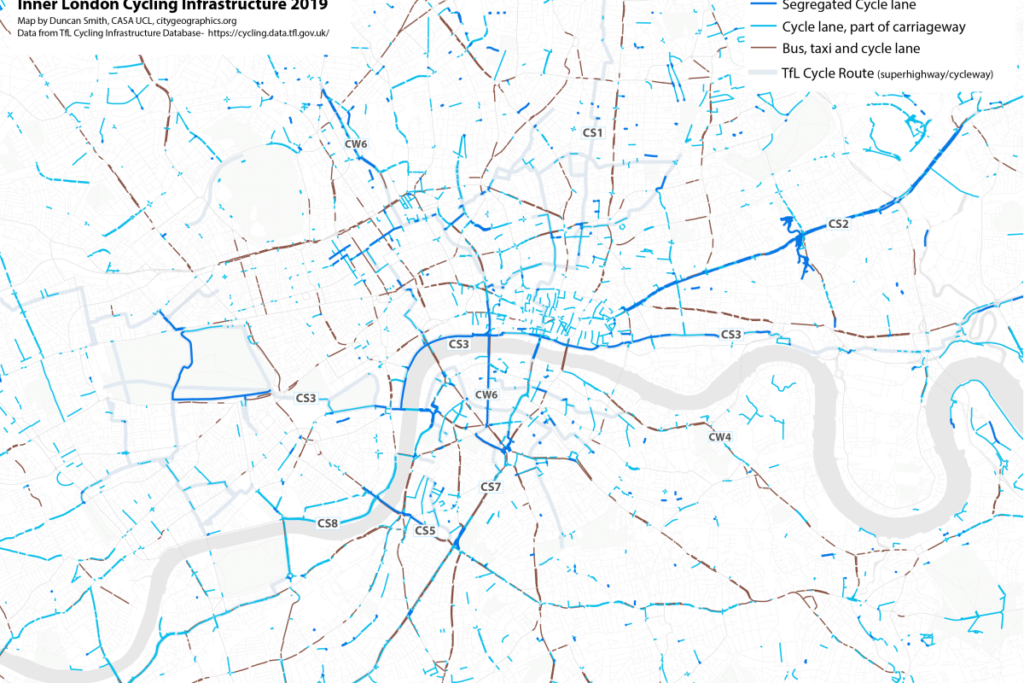

This is one of the reasons why many cities, both in Europe and North America, tend to have patchwork cycle infrastructure that starts in small sections, but struggles to establish a functional network. Installing and maintaining a fully connected network of fully separated cycling infrastructure exclusively is usually too expensive and/or doesn’t fit into existing road profiles. This is often where city administrations reach a stalemate in developing the cycle network: Various corridors of protected infrastructure disconnected from one another.

Source: https://citygeographics.org/2020/05/26/planning-a-cycling-revolution-for-post-lockdown-london/

What surprises many city officials is that only 20% of the Dutch cycle network is protected infrastructure, meaning the other 80% is mixed with motorized or pedestrian traffic. This is not because the Dutch are brave enough to cycle in high-volume fast-moving traffic. In reality, there’s more to it than that.

Throughout many projects and workshops, we often say that the best cycle network, in fact, starts with a good car network. You can draw new connections for the cycle network as much as you like, but every point in the cycle network that intersects with high-volume and high-speed motorised traffic decreases the likelihood that people of all ages and abilities will use it.

The Dutch have quite an apt word for this process: ontvlechten, or “disentanglement of the car network.” If I were the type to get an urban planning related tattoo, you’d see this word in big cursive letters splashed across my chest. Or maybe painted on my living room wall the same way that “Live, Laugh, Love” hangs above so many families’ sofas.

In all seriousness, this approach is absolutely crucial to achieving the calm, cycle-friendly Dutch urban city centres so many enjoy. ‘Disentangling’ the car network is accomplished through traffic calming measures on local streets to slow traffic, as well as modal filters that divert cars away from smaller residential or city centre streets and towards distributor roads designed for higher-volume and higher-speed traffic. This makes it faster to go around these areas rather than pass straight through them. Of course, this does not mean that cars are not allowed in the city centre, but rather it prevents cars from using small local roads as thoroughfares to the other side of town. This is reinforced by the fact that both the design speed and legal speed limit in almost all Dutch city centres is 30 km/h.

Description: Fully separated and protected cycling facilities are, in fact, quite rare in residential and city centre streets in the Netherlands. All thanks to effective management of traffic volumes. Mixed traffic between pedestrians, cyclists and cars is possible when speeds and volumes of car traffic are low.

Changing the car network is, of course, no easy task, so it’s no surprise that this step is often where cities get stuck. The easiest application of this lies in new developments, where transport networks can be drawn out from scratch. However small-scale pilot projects can also be tested in existing areas where traffic volumes and speeds are already relatively low. Many cities, from Barcelona, to Hackney, to Montreal, are experimenting with this, either at a neighbourhood scale, or just one street at a time, such as around school zones where children are at play.

30km/h zones are an increasingly hot topic in the transport planning world, but speed is only one factor of the equation. Managing traffic volumes is an often-overlooked step in establishing a safe cycle network. Even slow-moving traffic at high enough volumes can create conditions uncomfortable and unattractive for cycling in mixed traffic. Ultimately, if a city truly wants to make leaps and bounds in their cycle network, it’s crucial to look beyond only traffic calming and re-examine the car network. Finding opportunities to balance places to stay and spaces for flow to create what we call The Good Street is the perfect way to start this process – to practice ontvlechten themselves.

">

">Stephen Kurz

‘Though we are strongly influenced by our environment, effective urban design can help us make sustainable, healthy, and safe choices. Not because we’re more aware of our choices, but because we’re not. Good urban design makes the ‘right’ choice easy. To achieve this, I value non-traditional approaches to exploring and developing solutions to urban issues.’