Women Mayors Making a Difference

Women’s History Month may be over, but the importance of celebrating and prioritizing women in mobility does not end! Here at Mobycon, we want to highlight some of the amazing urban sustainability contributions that women have made today and in the past- in a few of the places our experts are working. We hope that these stories of impactful women mayors inspire readers to keep getting involved in sustainable mobility!

Valérie Plante, Mayor of Montréal

In 2017, 375 years after its founding, Montréal elected its first female mayor, Valérie Plante. With one year remaining in her third mandate, Valérie Plante leaves behind a substantial legacy. Recently, she officially announced that she would not return for a fourth mandate as mayor.

Says Université de Montréal professor Jean-Phillipe Meloche, “Valérie Plante has put Montreal on the map, not in terms of business, but climate change and public policy. The city is not just a place to do business, but a place to live. […] She has embodied an ideological transition.”

Regarding sustainable transportation, Valérie Plante has accomplished some honourable things for Montréal; she even fully embraced her title as “Madame Vélo” or “Ms. Bicycle” In English. To name a few notable things she did to improve mobility and people’s experience in the city:

- The “Réseau express vélo (REV) (Bicycle express network)” is the first bicycle highway in the city, having recorded more than 1.5 million trips last year. Once finished, the full REV will encompass 190km.

- Almost 70% of the 1000km bicycle network is winter-maintained, and Montréal doesn’t have easy winters!

- She is most proud of making the city greener, with a total area of protected green spaces that has doubled in size.

- More and more streets are now pedestrianized during the summer months, contributing to many local businesses’ success.

- Ending the nearly 20-year status quo of the Montréal metro with the initiation of the blue metro line extension.

- Reduce mobility poverty in the east by creating a bus rapid transit (BRT) line.

For all the mobility enthusiasts out there, she will certainly be missed!

–Arianne Robillard, Junior Integrated Mobility Consultant | Ottawa, Ontario

Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris

It would be not easy to overstate Anne Hidalgo’s impact on city cycling in this decade. Paris’s first woman mayor took office in 2014, and immediately launched an agenda to ‘Reinvent Paris’. The ambition evident in the title – to reinvent an old city with some of the most recognisable streetscapes in the world – was to become Hidalgo’s trademark.

Despite the street life of its celebrated boulevards and the reach of its iconic Métro, the city’s public realm remained profoundly dominated by moving and parked cars at the start of Hidalgo’s first term. Her team had moved quickly and, critics allege, unilaterally to reallocate space away from cars, and give it to people walking, cycling, wheeling, and sitting.

Not only physical space but clean air was appropriated as a matter of municipal interest in the ‘Paris Breathes’ (Paris Respire) plan. Starting in 2016, on the first Sunday of the month, certain zones in the city were closed to cars and opened to pedestrians and cyclists, while public transport and bikeshare were cost-free. For a short time, this was a way of achieving what could not yet be made permanent: an ‘experience machine’ through which tens of thousands of Parisians could see for themselves what their familiar streets would look and feel like without moving and parked cars. Anne Hidalgo staked her mayoralty on this logic, which was repeated in demonstrations of growing scale and political risk.

Controversy around her plans went hand in hand with well-funded opposition, especially from elites. Hidalgo’s team exposed itself to accusations of authoritarianism as they worked to circumvent the institutional structures that had, up to then, maintained a high degree of car dominance in dense, transport-rich Paris. However, her team’s insistence on creating tangible demonstrations of ideas, so that Parisians could judge for themselves, has broken obstructionist tactics, even though it sometimes required pushing through change in the face of legal challenges and local opposition.

Hidalgo’s long career in Socialist politics and her professional life as an inspector of fair working conditions have given her a keen sense of how easily important social questions can be reframed to the advantage of elites. Her administration’s work to create Covid-era coronapistes, an emergency network of cycling routes to relieve public transport, and to retain and expand these into a coherent cycling network as part of her second-term mandate to create a 15-Minute City, can be seen as a successful reframing of public space as a resource that must offer something meaningful to every resident, not just ‘car owners’ (or, for that matter, ‘cyclists’).

In less than a decade, this leadership level has made Paris the quickest and most profound example of a large city’s transition towards sustainable mobility anywhere in Europe.

–Brett Petzer, Mobility Advisor | Delft, The Netherlands

Tory Whanau, Mayor of Wellington

This mayor in New Zealand, the home of Mobycon’s new Pacific office, has made great strides in improving Wellington’s cycling infrastructure. When the Golden Mile project, which would redesign Wellington’s main drag to include space for a cycleway, outdoor dining, trees, and pedestrians, lost its funding, Tory Whanau’s administration redesigned the project and found new sources of support. The contract for the project has been signed, and is scheduled to begin construction in late April 2025.

This was only the latest of a series of infrastructure achievements in Wellington over the past few years. The city won a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies to explore a network of off-road cycleways that allow people to experience more of the area’s natural beauty while cycling. Out of 270 applicants, it was one of only 10 to receive the award. Whanau also accepted the Breakthrough Biking City of the Year award in 2023, which was awarded for the ambitiousness of the Golden Mile project and the 166 kilometers of cycleways that the city plans to build in the coming years. All this after less than 3 years in office! We’ll keep our eye on Wellington and hope to work with Whanau’s administration soon.

–Lennart Nout, Manager of International Strategy | Auckland, New Zealand

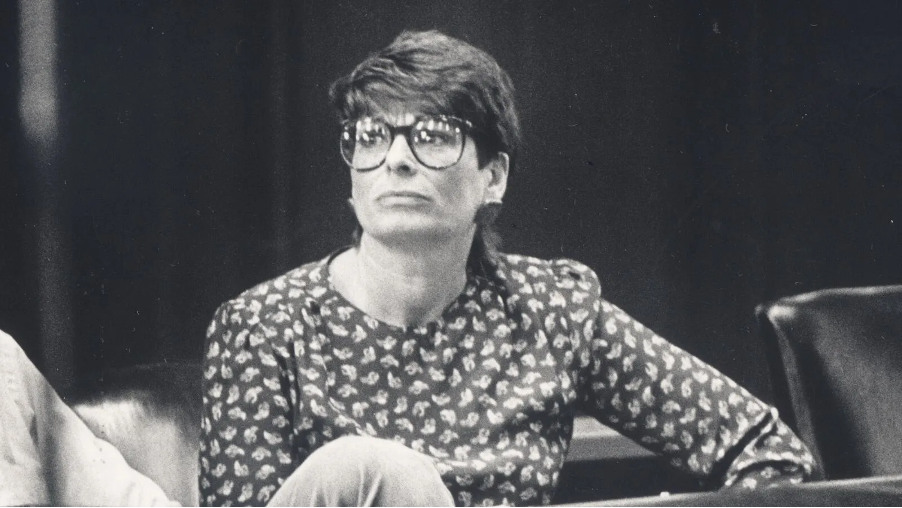

Vera Katz, Former Mayor of Portland

“A great city never sleeps. A great city never stands still. A great city shares its vision with its community . . . A great city (takes risks) . . . But without taking those risks, you will never become a great city.”

“More women need to get involved. They view the issues differently. I hate to admit it, but we do. There is a lot more empathy, a lot more understanding of how all the dots connect.”

Vera Katz was mayor of Portland (where we recently opened our new American office) from 1993 to 2005. She’s the only person ever to have won three terms in the office and is known as the city’s last successful mayor. Before that, she was the first woman to be the Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives, where she set the same three-term record. She introduced the first bill in the country that would have extended the protections of the Civil Rights Act to include LGBT people. Katz’s life story, as a Holocaust refugee, is more deserving of a book than a blog post, and we found countless incredible stories about her while researching.

She was responsible for Portland’s most prominent monument to active transportation, the Eastbank Esplanade, which today bears her name. Her administration’s master plan for the city’s waterfront led to the construction of Tilikum Crossing, the first car-free bridge in America. The Portland Streetcar was also built during her time as mayor, with less than 5% of the cost covered by the federal government. She even led the charge for a direct light rail line from downtown to the airport (something New York and Los Angeles are still trying to figure out). The line was first proposed in 1997, started construction in 1999, and opened in 2001, without federal or state funding or additional property taxes. Such an achievement would be unimaginable in America today.

She also facilitated the redevelopment of disused industrial areas now known as the South Waterfront and the Pearl District. These neighborhoods are unique in the West for their integration of walkability, transit, and bike infrastructure. They helped to delay Portland’s housing crisis and have inspired other brownfield redevelopments across North America. For the homeless, her administration legalized Dignity Village, a self-governed community on city-owned land. A troubled part of downtown got new museums and the world’s foremost Chinese garden. Her projects reinforced each other: the South Waterfront is connected to the Pearl District and light rail by the Portland Streetcar, the Eastbank Esplanade by the Tillikum Crossing car-free bridge, and its hospital campus is connected to another by the Portland Aerial Tram. About her projects, historian Chet Orloff said:

“They’re all about making this place more livable, and they’re all very design oriented … the finest legacy this mayor left is this collection of buildings and places. They really have become places.”

Vera Katz was exactly the kind of woman we need right now in the mobility sector and in every part of American society: someone who, given every opportunity to keep her head down and climb the corrupt ladder, instead calls out injustice wherever she sees it. Bringing some pots and pans along doesn’t hurt.

–Riley Coler, Sustainable Mobility and Marketing Intern | Delft, The Netherlands

Want to learn more about our services and what we’re up to? Follow us on Social Media for the latest updates, insights, and projects.